|

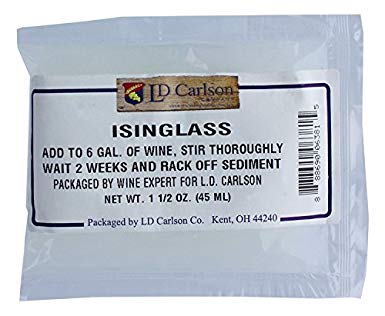

“We’re putting an ingredients label on our packaging,” the full-page ad in a Sunday edition of the LA Times reads. “Because it’s the right thing to do. Because you deserve to know your beer’s ingredients.” It’s an ad for Bud Light. Not a small-production craft beer, which one might expect to tout this sort of credential. But for “America’s favorite light lager,” the stuff of college parties and tailgating. The beer giant also put out a press release announcing the move. In the months following, a heated debate about what should and shouldn't be included in the labels of our favorite adult beverages has been brewing (pardon the pun).  Bud Light takes a stand on ingredients labeling. Photo: Twitter @BudLight Bud Light takes a stand on ingredients labeling. Photo: Twitter @BudLight Ingredients labeling has become the norm in the food industry because it’s required by the FDA. However, to date, the adult beverage industry does not require ingredients to be listed or nutritional information outlined on labels unless a specific health claim is being made such as “low carb” or “low calorie.” In fact, current law allows for a laundry list of additives -- some of which sound, well, distinctly chemical, that can be used but don't need to be included on the label. While we are seeing the occasional brand volunteer these details, there are no current regulations requiring alcohol brands to go beyond the basics on their labels. This includes the wine industry. It’s one thing to list “water, barley, rice, hops,” on your packaging in the name of transparency, as Bud Light has now promised to do. But what if your ingredients include things that are barely pronounceable, even if they are essential parts of the winemaking process and totally natural? As consumers increasingly demand not only transparency, but food made from ingredients that don’t look like they belong in a lab, how does the wine industry stand to fare? The issue is clearly a sensitive one.  Amanda Thomson believes in full transparency when it comes to wine labeling. Image courtesy of Thomson & Scott. Amanda Thomson believes in full transparency when it comes to wine labeling. Image courtesy of Thomson & Scott. Amanda Thomson, Founder and CEO of Thomson and Scott, makers of a line of low-sugar, vegan sparkling wines, is outspoken on the issue of transparency in wine labeling, pressing the wine industry to introduce stricter rules and regulations on this front. “We all want to know what’s in our food. Why aren’t we asking what’s in our wine?” While wineries like Ridge Vineyards and brands like Atlas Wine Co. are making a point to list ingredients on their labels – Ridge Vineyards’ 2016 Paso Robles Zinfandel boasts nothing but “Hand-harvested grapes; indigenous yeasts; naturally occurring malolactic bacteria; oak from barrel aging; minimum effective SO2” on its back label – others don’t feel it’s a necessary or particularly good thing for the industry. “In my opinion, it’s really a can of worms,” says Master Winemaker Jon McPherson, who makes wine in both Temecula Valley Southern California Wine Country and Texas Hill Country. “I would need to include a small dissertation with each wine, explaining how the additive used actually worked, precipitated out, or was removed via filtration, and why we did it – so the consumer could have a wine that was consistent, varietal and worth the money they spent.” How does the average wine-loving consumer feel? For Lindsay Stewart, a New York City-based entrepreneur and mother of two, it depends. “Unless there are things winemakers are putting into wine that would totally derail the industry and blow the lid off some cover-up, I don't think I'd really care about what ingredients go into the wine,” she says. Nefarious plots aside, it’s helpful to understand what is potentially added during the winemaking process, in order to dissect what a move for stricter labeling laws could ultimately mean. There is a romance to winemaking, and many consumers don’t understand the entire scientific – and artistic – process from grape to glass. At its core, winemaking involves turning the sugars in grapes into alcohol via the introduction of yeast. However, there are certain interventions in the winemaking process that winemakers can use to not only stabilize the final product, but make it more commercially appealing to their target consumer. Beyond the addition of everyone’s favorite punching bag – sulfites – winemakers frequently use ingredients like egg whites, gelatin, casein (a milk-derived protein), isinglass (a protein derived from fish bladders), bentonite (an adsorbent clay) and many others during the fining and filtration process. Winemakers have further options available to them – ingredients like the infamous “Mega Purple,” a sweet, syrupy grape concentrate used to enhance a wine’s color and “roundness,” and other additives like powered tannin and oak flavoring. These tricks of the trade are no secret – at least not in the winemaking world. But you’re likely not going to hear about them on your tour of the winery or in the tasting room. This is perhaps where the issue of transparency for the consumer gets tricky. Do we really want to know? Like being faced with the results of a full body scan showing strange and possibly benign irregularities, what do we do with that information once armed with it? “First, let me say this: It is nature’s course to make ALL wine vinegar, and without man’s intercession, a juice that ferments with wild yeast will hit a point where it is a good, drinkable wine, and then, without any help, continue on through to bacterial spoilage and go to vinegar,” adds McPherson. In other words, all those things that may look scary on a wine’s ingredients list – if the industry required one – are, arguably, necessary for producing a wine that is shelf-stable. Like being faced with the results of a full body scan showing strange and possibly benign irregularities, what do we do with that information once armed with it? The natural wine movement, in which wines are made with little to no intervention, is still a relatively niche market and comes with its own set of controversies that could fill up several dozen articles.  Winemaker Olivia Bue pulls barrel samples. Winemaker Olivia Bue pulls barrel samples. Fellow Temecula Valley winemaker Olivia Bue of Robert Renzoni Vineyards agrees with McPherson. “There are a few additions we do add, such as bentonite, for fining and clarifying purposes prior to bottling,” she says. “It’s important for consumers to understand that many additions are designed to bind with an oppositely charged organic compound in wine, then drop or precipitate to the bottom of the tank to be left behind after racking. In other words, they leave behind no traces of material.” For those winemakers going beyond basic fining, filtration and stabilizing agents, and adding things designed to enhance the flavor, color or sweetness of a wine, it’s understandable why a winemaker may not want the industry to push for label reform, for fear these tactics are painted as “cheating.” But many wholesalers and retailers see transparency as a powerful selling tool. “People should know what they are consuming,” says Jonathan Porter, New York City Director of Sales for Massachusetts-based importer & distributor MS Walker. “I think it’s important to the buyer and consumer. [Not doing so] gives an unfair advantage to people who artificially manipulate and cut corners. If someone is operating with minimum intervention, then they should be able to distinguish themselves from manipulated projects. Does it make for a better bottle of wine? I can’t speak to that; but it is important for the producer, the buyer and consumer, so the wholesale sector is at a competitive disadvantage if they aren’t able to embrace that space.” But how much transparency is enough, and how much is too much? Is there such a thing? In 2016, the Beer Institute launched the “Voluntary Disclosure Initiative,” an opt-in program in which beer companies would include a servings facts statement and disclose ingredients on either the label, the secondary packaging, a reference to a list on the website, or through a QR code. Most major players in the beer space, including Anheuser-Busch, MillerCoors and HeinekenUSA have opted in to this initiative. There is currently no equivalent initiative in the wine industry. To date, there are varying levels of voluntary disclosure. Some wineries choose to tell the consumer everything about the wine itself, from the grape blend to the specific oak treatment. Others are opting to go a step further, tacking on the nutritional information chart we are so used to seeing on our packaged food items. Whether or not we need to pull back the curtain to completely reveal the wine industry’s less sexy parts, there is likely some room for improvement. In addition to ingredients labeling, wineries in many regions generally aren’t even required to list what specific grapes are in the bottle. While this isn’t an issue in most Old World wine regions because of the strict appellation laws in play that govern precisely what grapes, winemaking techniques and alcohol levels are required in order to label a wine in a certain way, many New World wine brands play fast and loose when it comes to what they include – or don’t include – on their labels. Some seem almost deliberately obscure, featuring nothing more than stories about the winery or other offbeat verbiage that tells the consumer absolutely nothing about the wine itself other than it was branded by some very creative people. Gary Itkin, GM of the popular and ultra-consumer-friendly retailer Bottlerocket in New York City, has mixed feelings on the issue of transparency, and says the industry should perhaps start with requiring basic information on the wine label about its origins and general composition. “Everyone knows that wine is about 110 (and up) calories per glass, and from a retailer’s point of view, no one need be reminded that there are 5 servings in a bottle,” he says. “However, if a standardized label were affixed to the back of every bottle that clearly stated the actual producer, the grape varieties used, the farming practices, g/l of sugar, total acidity and SO2, that might be something. If you tried to list the additives used, for many brands the label would stretch longer than the bottle, but the inclusion of the phrase ‘contains additives’ could be used along with perhaps a QR code or augmented reality to view the complete list.” Bue also feels some basic information should be required. “I do feel any residual sugar above 0.5 g/100ml should be written on the label for health reasons. Many consumers gravitate naturally to sweeter wines without having knowledge of the higher caloric value.” Thomson is a big believer in stating sugar levels. She has built her brand around the need for lower-sugar options when it comes to sparkling wine, noting that many of the top brands on the market contain as much as 12-15 grams of sugar per liter, but the average consumer is not aware of this as technically the wine can still be classified as “Brut,” or the counter-intuitive “Extra Dry.” By contrast, her Prosecco contains 7 grams of sugar per liter, a fact that she states clearly on the bottle and website. As with any other food or beverage we put in our bodies, we would all agree that we would in theory rather purchase a well-made product containing minimal sketchy ingredients that won’t harm us or pack on any extra pounds. Whether we actually live by that code 100% of the time is another story.  Photo by Bruce Mars from Pexels Photo by Bruce Mars from Pexels According to a 2018 article published in the Washington Post, several studies have shown that nutritional information posted on restaurant menus has little impact on consumers’ actual caloric intake. Some dieticians have even suggested that posting this information can have a triggering effect for those suffering from eating disorders. However, the Post points out that, aside from encouraging consumers to eat better, menu labeling laws are also aimed at getting food producers to make lower-calorie products, and that they may be succeeding in at least this piece of the goal. Whether or not consumer behavior follows the same patterns when it comes to alcohol remains to be seen, but if labeling laws encourage winemakers to produce the cleanest, least-manipulated and sustainable products possible, one could argue in favor of the practice, regardless of its impact on actual consumer behavior. Roger Bohmrich is a New York-based Master of Wine – one of the first Americans to earn this prestigious title. He, too, sees the danger of too much transparency. “The mostly unjustified concerns about sulfites show the unintended consequences of ‘tell-all’ labeling,” he says. But he does see value in this movement toward transparency in the pressure it puts on wineries to employ sustainable or organic practices in the vineyard. “The larger question centers on the vineyard and the chemicals that might be employed, as with any agricultural crop. It's virtually impossible to avoid chemicals entirely, simply because they may be present in the groundwater itself. I am very much in favor of organically or biodynamically grown grapes, where that is economically feasible, and those approaches are slowly communicating added value to wine drinkers. For most wines, on the other hand, I'm afraid we have to live with trace additives, as we do with apples, peanut butter, or bread.” At the end of the day, it’s tough to argue against transparency for the consumer, especially if it encourages an increase in quality products. However, the real question surrounds what defines transparency, and what its limits should be. “Does [greater transparency] de-romance the wine aisle? Perhaps,” says Stewart. “Would I drink less wine? Probably not. Would I change which wines I purchased based on these labels, but still stay in the wine aisle? Probably!” Notes McPherson, “None of the added ingredients go beyond a brief interlude and then are dispatched via settling or filtration. Or, we are simply augmenting what is already there. Tannins are already present. Sulfites occur naturally as a yeast by-product, and we just boost their presence so that the wine will be shelf stable longer. What did I add that wasn’t already there? If it isn’t detected was it really ever there?” Deep. This debate is only going to intensify as more and more big brands like Bud Light put a stake in the ground on the matter. But it’s probably best to pour ourselves a glass or two before pondering these sorts of heavy, existential questions any further.

1 Comment

|

AuthorDevin Parr writes about wine -- drinking it, making it, life with it, traveling for it and the business of it. She also dabbles a bit in careers and parenting. Archives

January 2021

Categories

All

|

Company |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed